Whole-of-government adoption of generative AI

This section outlines findings in relation to the challenges experienced by the Australian Public Service (APS) in adopting Microsoft 365 Copilot and its broader lessons that are applicable to the APS’ future adoption of broader generative AI.

Key insights

There are currently challenges with the integration of Copilot with products outside of the Microsoft Office suite, limiting its potential benefits to agencies that use non-Microsoft products.

Poor data security and information management processes could lead to Copilot inappropriately accessing sensitive information.

Agencies should also note that that some Copilot functionality – in particular for Outlook – requires the newest versions of Microsoft Office products.

Tailored training in prompt engineering and agency/role-specific use cases were needed to build capability in Copilot. A range of methods were used to upskill staff, including formal training sessions and informal forums. Managers also require specific training to help verify Copilot outputs.

There are cultural barriers that may be impeding the uptake of Copilot ranging from the perceived negative stigma of using generative AI to a lack of trust with generative AI products.

Further clarity on personal accountabilities for Copilot outputs alongside greater guidance on the extent consent and disclaimers are needed for generative AI use are required to improve adoption.

Given the evergreen nature of generative AI, there is a need for agencies to engage in adaptive planning while setting up appropriate governance structures and processes that reflect their risk appetites.

There are key integration, data security and information management considerations

Copilot may require plugins or other connectors to ensure seamless integration across an organisations’ technology stack.

… their labelling of classified or sensitive information does not work with Copilot as they use the third party Janusseal.

Copilot is available through applications within the Microsoft 365 ecosystem. However, to access data or applications that sit outside this ecosystem, organisations need to leverage plugins or Microsoft Graph connectors to create extensibility.

A small number of pre-use survey respondents and DTA interview participants raised an issue of the lack of Copilot integration with third-party software in particular with Janusseal, a software that enables enterprise-grade data classification for Windows users, and JAWS, a computer screen reader program that allows blind and visually impaired users to read the screen either with a text-to-speech output or with a refreshable Braille display. Issues with JAWS integration comprised 16% of total issues recorded in the issues register.

The lack of integration with Janusseal creates a potential limit to the usefulness of Copilot for APS staff regularly interacting with sensitive information in organisations where data classification is managed through third-party providers such as Janusseal. Interviews conducted by the DTA noted a lack of integration with Janusseal could lead to APS staff gaining access to information they did not have permissions for. Microsoft has advised that this is a third-party labelling issue, not a security issue, and that Copilot has an in-built fail safe to protect against this issue. It should be noted that such integrations were out of scope for the trial and Microsoft has further advised that a more permanent fix to the labelling issue is in the pipeline (Microsoft 2024).

The newest versions of Microsoft Office products were required to enable some Copilot functionality

Copilot is available in Outlook, enabling users to more efficiently manage their inboxes. Newer features of Copilot were initially released with the new version of Outlook, rather than classic Outlook.

The integration of Copilot with Microsoft Outlook was frequently raised as a key issue as Copilot features in Outlook were only available with the newest version of Microsoft Outlook or the web version of Copilot. Microsoft initially planned to release Copilot updates to the new version of Outlook and later for classic Outlook. Focus group participants often lamented not being able to access the full capabilities of Copilot as they did not have access to the new Outlook. One trial participant noted through the issues register that, ‘classic Outlook will only support the bare minimum Copilot features’.

Focus group participants also reported that the online versions of Microsoft Office apps had a poorer user experience than the desktop applications, which dissuaded them from using Outlook online. For agencies without the newest version of Microsoft Outlook, the overall potential benefits of Copilot would likely be significantly reduced and restricted to other use cases such as the summarisation and drafting use cases in Microsoft Word and Teams.

Poor information, data management practices and permissions resulted in inappropriate access and sharing of sensitive information.

Agencies classify their data and apply permissions to ensure access is limited to authorised personnel and that staff understand a document’s security levels.

Their information management in SharePoint is not great which has resulted in end users finding information that they shouldn’t have had access to, though this is a governance and data management issue - not a Copilot issue.

Use of Copilot enabled some participants to access documents that they should not have had permission to access. Trial participants raised instances where Copilot surfaced sensitive data that staff had not classified or stored appropriately. This was largely because their organisation had not properly assured the security and storage of some instances of data and information before adopting Copilot. Without the appropriate data infrastructure and governance in place, the use of Copilot may further exacerbate risks of data and security breaches in the APS.

Tailored training in prompt engineering and use cases is needed to build capability and confidence

Prompt engineering and understanding the information requirements of Copilot across Microsoft Office products were significant capability barriers for trial participants.

There are 2 key skills required for users to realise the benefits of Copilot: writing effective prompts and understanding the different information structures that Copilot needs across different Microsoft products.

[Writing a good prompt is] a new concept … people did not know how to do that

Prompt engineering was viewed as one of the highest learning curves among focus group participants. Most focus group participants mentioned that prompt engineering is not a widely held skill in the APS and that it takes time, training and consistent experimentation to develop it. They recognised that tailoring prompts to specify the style, tone or format of outputs greatly enhanced the effectiveness of the tool. Without this capability, Copilot would be more likely to return generic, contextually unaware responses that were ill-suited to the user’s needs.

Another barrier to prompt engineering capability uplift may also be the consistency of performance attributed to the limitations in the large language model that was used throughout the trial. Until May 2024, a bespoke version of ChatGPT-3.5 was the model supporting Copilot, which was then updated to ChatGPT-4 Turbo. This update significantly increased the available characters or ‘input length’ that users could use to prompt, as well as an increase in the output length of Copilot’s response. This allows Copilot to consume more information and potentially provide more accurate or more detailed responses. Understandably, this capability challenge was more apparent among focus group participants with little or no prior experience with generative AI. These participants acknowledged that they did not know how to prompt effectively and the usefulness of Copilot was diminished as a result.

The capability to derive benefits from Copilot were further challenged by differing Copilot information needs across Microsoft products. For example, while Excel requires data to be inputted in tables for Copilot to recognise the inputs, conversely it cannot recognise data included tables in Word.

Focus group participants also remarked on the difficulties in preparing data in Excel for effective prompting. The learning curve for Excel appears particularly high as trial participants who used Excel noted that it often responded to prompts with a message that it could not complete the requested action.

As such, the learning curve to effectively use Copilot is further heightened by not only the need to learn new skills such as prompt engineering but also the need to learn how to use Copilot differently across MS products. Managers trust their teams to verify outputs but lack the ability to identify outputs themselves.

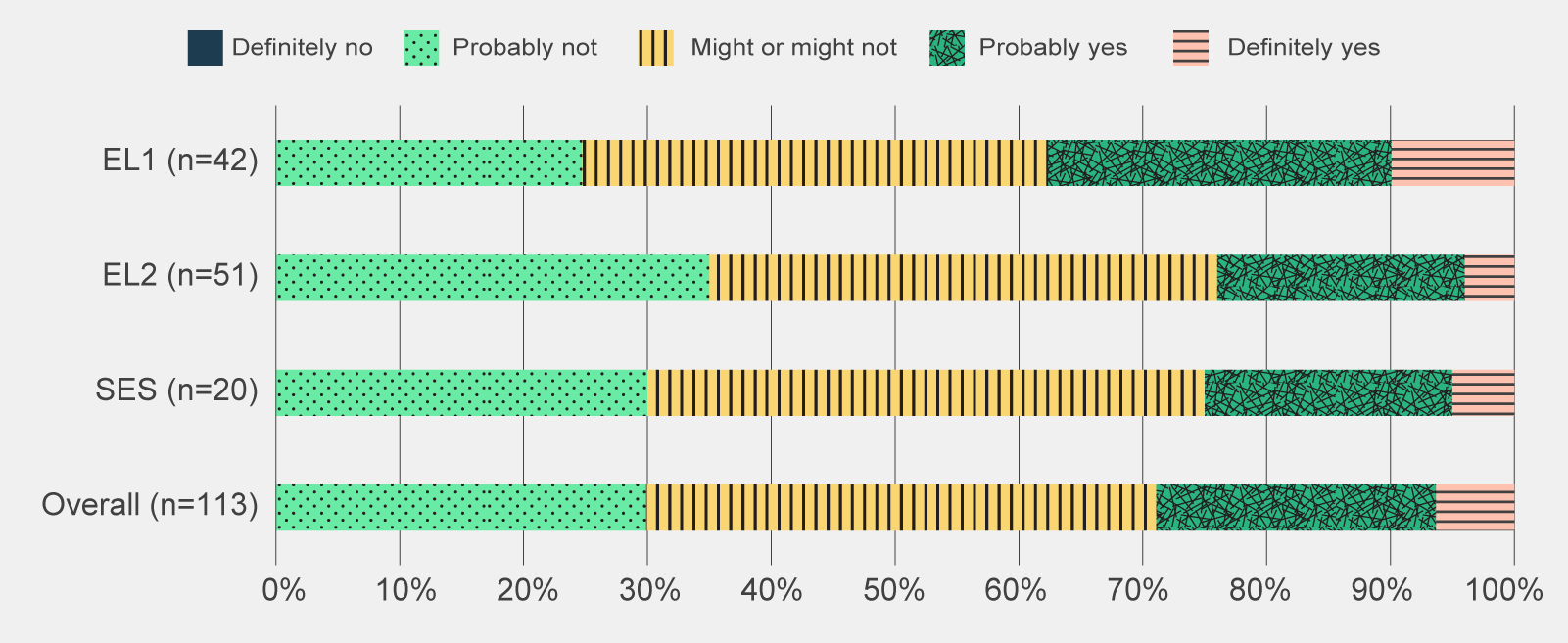

Whilst managers may trust their staff to verify outputs, the majority of managers could not recognise Copilot outputs. Only around 36% of managers in the pulse survey were confident they could consistently identify the difference between outputs produced with Copilot and those produced without.

There are concerns that inaccurate or poor verification of Copilot outputs increases the risk of inaccurate policy advice. Given the likelihood that managers cannot identify Copilot-generated outputs, there is a pressing need for staff to critically review content before forwarding it on for approval. The lack of awareness may point towards the need for further training in identifying the hallmarks of AI-generated content or the use of disclaimers when generative AI has been used.

Effective communication ensures clarity of roles, responsibilities and expected behavioural norms

Lack of clarity and communication regarding information security reduced trust in Copilot.

To effectively manage the personal, sensitive and restricted data it is entrusted with, the APS has strict data and information sharing and storage requirements. Software providers are required to meet these expectations to ensure data and information remains secure. Many generative AI tools house data in America, which does not align with on-shore data storage requirements in the APS.

While Microsoft had provided assurance that Australian user data is housed in Australia and is not used for training models, it appears that trial participants still had varying degrees of understanding and confidence regarding the safety of data and information inputted into Copilot. While some focus group participants remarked that their agency banned the use of sensitive information in Copilot, others noted their agencies were confident in Copilot’s data security arrangements and allowed sensitive information to be used.

Future implementation efforts should provide clarity around information and data security, as well as protocols and guidance as to what information is inputted into generative AI tools.

There may be negative stigmas and ethical concerns associated with using generative AI.

Agencies provided different levels of guidance and encouragement around Copilot and generative AI use more broadly. As a result, there are likely to be differing degrees of openness with using generative AI across organisations.

Our positive culture around use came from the top

Focus group participants expressed a variety of views in relation to their agency’s openness in using generative AI in their work. Three focus group participants voiced concerns about a perceived stigma or negative reaction if they openly acknowledged their Copilot use. The stigma originated from a belief that Copilot negated the need for staff to use their own critical thinking skills – thereby suggesting that Copilot encouraged laziness.

In comparison, in agencies where leaders actively encouraged and expected Copilot use, focus group participants reported positive reactions towards Copilot and uptake. Two focus group participants from different agencies reflected that publicly communicating ways that senior leaders effectively used Copilot drove positive sentiment. For example, one focus group participant from the DTA mentioned that their chief executive officer (CEO) showcased how he had been using generative AI, which led to a perceived uptick in usage within the agency.

Trial participants working in policy roles voiced concerns regarding the use of Copilot in producing policy advice, believing that this function should be solely human-led. These trial participants viewed the use of AI to support the development of policy could lead to a deterioration of the trust and confidence of the public and create broader ethical issues.

Most of my work is delivering outward facing policy documents and positions. I struggle to use Copilot in my day-to-day work as it is a conflict and an ethics issue to have government policy positions created by AI.

Related were the fears of inputting information into Copilot that were sensitive in nature. In focus groups, participants from policy job families vocalised a well-founded hesitation to use Copilot on any remotely sensitive agency information which was regularly reinforced by their agencies.

Varying levels of stigma around AI use suggests that leaders will be critical in both championing its use but also reducing any negative associations within agencies in the use of generative AI.

Some participants feel uncomfortable about being transcribed and recorded and perceive that they are being pressured to consent.

While the transcription functionality provides benefits in producing meeting summaries, focus group participants have expressed discomfort with being recorded and transcribed. Three focus group participants voiced concerns about the broader implications of real or perceived staff coercion to accept transcription if it becomes a norm.

An additional 2 focus group participants raised concerns around whether there would be an expectation that all meetings – even informal ones, will be transcribed. In response to these concerns, some agencies have chosen not to permit transcriptions.

As use of generative AI tools increase across the APS, considerations around etiquette and what constitutes normal or acceptable use will need to be worked through. Concerns around transcription highlight the need for clear guidance, processes and expectations from agencies. This should include the possible ramifications of transcription, ranging from legal requirements through to job expectations. In developing this guidance, agencies need to listen to, consider and respond to staff concerns.

Certainty of legal and regulatory requirements is needed to ensure responsible use of generative AI

There is a need for clearer guidance on the accountability for Copilot outputs.

As generative AI becomes more advanced, questions arise around the extent to which a human is accountable for the output and whether they can attribute responsibility to generative AI. One of Australia’s 8 AI Ethics Principles highlights, ‘people responsible for the different phases of the AI system lifecycle should be identifiable and accountable for the outcomes of the AI systems, and human oversight of AI systems should be enabled’.

While focus group participants unanimously agreed that users of generative AI are ultimately accountable for the output, they noted accountabilities were not always clear particularly when users were unable to verify the suitability of the inputs used. For example, in the instance whereby a staff member unknowingly uses sensitive data to produce a public-facing document, it is unclear if the accountability lies with the person who stored the data, the person who created the document, the person who reviewed and approved the document or if all these parties should be held accountable.

There are likely many more instances whereby the remit of persons accountable where generative AI has been used is unclear and will require multiple agencies to work together to provide cohesive and aligned advice on accountabilities and expectations regarding the use of Copilot and generative AI more broadly.

There is uncertainty around communicating Copilot’s use with the public.

The APS is required to safely manage personal, sensitive and restricted data. Additionally, the public expect their data to be appropriately managed and used. In the wake of the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme, public scrutiny around the APS’ use of technology and automation to support decision-making is particularly high.

Focus group participants expressed uncertainty regarding whether informed consent from customers is required before their data and information could be used in Copilot. For example, focus group participants were unclear whether consent was required from customers to use customer information to draft a letter responding to a customer query.

One focus group participant noted that customers may worry about Copilot use given wider societal concerns around AI security and output quality. They remarked that despite certainties around information security, members of the public will likely hold a range of preferences, including a preference that generative AI does not access their personal data and information.

Similarly, there is also a lack of consensus as to whether Copilot users should provide a disclaimer to the public on Copilot use. Five focus group participants believe that the public should be able to know if content is AI generated to increase transparency. However other focus group participants were concerned that disclaimers could contribute to a decline in quality as users would reduce their diligence in checking outputs as they could attribute errors to generative AI use outlined in the disclaimer.

Public concern about security and protection of personal, sensitive and restricted data is a key consideration as the APS moves forward with generative AI tools. It is likely that guidance will become more available as regulatory frameworks are implemented by relevant bodies. Agencies should consider privacy laws and potential customer implications if generative AI is exposed to this data to determine a responsible approach to this challenge.

It is unclear whether transcriptions are subject to Freedom of Information laws.

Government agencies are subject to Freedom of Information (FOI) requests which give people the right to request access to government-held information.

Whether meeting transcription outputs and other outputs produced by generative AI were subject to FOI requests, was a question raised by focus group participants. Two focus group participants expressed concerns that if meeting transcriptions are subject to FOI requests, it could hinder open expression and communication during meetings, thereby decreasing human connection and collaboration. Other jurisdictions, such as the Victorian Government have been explicit that, ‘records created by or through the use of AI technologies are public records and must be managed in accordance'.

Additionally, 2 focus group participants raised concerns that the transcription may erroneously attribute statements or misrepresent the conversation.

The questions and concerns raised by participants during focus group discussions indicate that APS staff would benefit from clear communication on FOI requests in relation to generative AI produced outputs including any safeguards needed to ensure accuracy in its transcription.

Adaptable planning and clear roles and responsibilities is needed

There is a need to ensure the most appropriate level of governance is in place that is aligned to the risk appetites of agencies.

The adoption of generative AI poses significant governance challenges as several agencies hold notional responsibilities for different aspects related to generative AI. For instance, the responsibility for information management and privacy lies with the Office of Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) while DTA was responsible for the implementation of the trial, supported by the AI in Government Taskforce.

There should be some concerted effort to make sure that the privacy considerations are considered across government because they're there's going to be commonalities.

The complexity of the issues related to generative AI led to confusion amongst trial participants in seeking the responsible agency to provide relevant advice. Three focus group participants responsible for their organisation’s implementation of Copilot highlighted a lack of whole of government advice on areas such as privacy, records management, and intellectual property. These focus group participants had hoped that the National Archives of Australia, Intellectual Property Australia or the DTA would have provided more information.

While there was confusion regarding advice on key issues related to Copilot, there was considerable contestability regarding the overall trial’s approach to risk management. Some focus group participants thought that individual agencies should be responsible for their governance and risk management processes and did not see the additional value of having more governance bodies for the trial.

Two focus group participants responsible for their organisation’s rollout believed it was beneficial to create their own risk register and privacy impact assessments (PIAs) rather than relying on the existing risk management processes in the trial.

The experience of the trial brings to light the differing risk appetites of agencies across the APS and that while centralised advice may be useful, and indeed in demand, centralised approaches to risk and governance may not be aligned to agency’s needs.

There is a need for detailed but adaptive implementation planning.

The DTA led the rollout for the Australian Government trial of Copilot, supported by the AI in Government Taskforce, which included representatives from other agencies such as Services Australia and DISR.

The DTA demonstrated agility and pace in the way they led the trial, effectively responding to the rapid implementation approach required. Discussions with focus group participants highlighted the challenges of rapid implementation with new technologies, noting that the recency and evergreen nature of the technology, inherently led to a continual need to review and develop governance and risk management approaches.

Experiences from the trial highlighted the importance of time spent planning for the rollout of complex technologies such as generative AI. However, the nature of generative AI also requires an adaptable and continually updated approach to adoption that considers the evergreen nature and changing risk profiles of generative AI.

Reference

- Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (2024) ‘Copilot for Microsoft 365; Data and Insights’, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Canberra, ACT, 12.

- Microsoft, (2024) Internal communication between the Digital Transformation Agency and Microsoft’.